The US-China Tech War

Phoebe Goh

(09/02/2023)

9 min read

In a surprising turn of events, Huawei Technologies made a comeback to the smartphone market in August with a 5G model that could compete with Apple’s iPhone. This development was unexpected to U.S. policymakers, who believed that the sanctions imposed by Washington had significantly impacted Huawei’s market competition.

The US-China tech war is steering in a direction that is harder for us to predict as both parties are moving at break-neck speed to counter each other’s strategies in a bid to slow down the advancements in technology.

As Huawei is poised to reestablish its global foothold in the smartphone, smart device, and telecommunications markets this year, it’s a wake-up call for U.S. policymakers. It’s clear that continued sanctions are having less of an impact on hindering Huawei. This situation should provoke a reevaluation of America’s approach to the tech war.

Huawei’s rebound proves limitations of sanctions strategy

Analysts predict that Huawei could distribute up to 100 million phones this year. While this number is still behind Apple’s and Samsung’s achievements or Huawei’s own 2019 peak of 240.6 million units, it would represent a significant recovery from the 30.5 million units shipped in 2022. This could potentially place Huawei back among the top five global smartphone brands.

Despite the U.S. pressure, Huawei’s original telecom equipment business has shown resilience, maintaining its global market share since 2019. This can be attributed largely to Huawei’s significant role in developing China’s 5G networks. The expansive domestic market of the company has helped it compensate for losses in markets where Huawei’s operations have been restricted due to U.S. lobbying efforts citing security risks, such as in Australia.

As the telecom equipment venture remains stable, and with the resurgence of phone sales and the launch of new lines of business like automotive systems, Huawei’s revenues increased by 9% to over 700 billion yuan ($97.7 billion) in 2023, a level last seen in 2020.

This success extends beyond Huawei, indicating that Chinese companies are beginning to competitively manufacture advanced semiconductors on a large scale, in spite of U.S. efforts to limit the growth of this sector.

Last year, China’s leading contract chipmaker, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp. (SMIC), demonstrated its ability to construct sophisticated processors that are compatible with the microchips in Huawei’s new high-end Mate 60 Pro model. If Huawei manages to meet its target of shipping at least 60 million phones this year, it will serve as a crucial benchmark for China’s increasingly independent semiconductor production industry.

Huawei’s rising phone sales may elevate its self-developed HarmonyOS to become China’s second-most popular operating system, potentially surpassing Apple’s iOS, according to some projections. HarmonyOS NEXT, the latest version, signifies Huawei’s complete independence from Android, requiring app developers to create new versions of their products for HarmonyOS compatibility. Already, HarmonyOS is utilised on about 800 million devices, and over 200 popular Chinese apps have been adapted for it.

As state-owned businesses and government organisations in China might quickly adopt HarmonyOS, this could only be the beginning. If China faces stricter sanctions from Washington, the adoption could accelerate further. With a self-reliant semiconductor supply chain and most Chinese devices running on domestically produced operating systems, Washington’s influence over China’s technology sector could be significantly reduced.

Why are US sanctions seemingly ineffective?

The limited impact of U.S. sanctions can be attributed to their incremental implementation, which allowed Huawei to strategically stockpile resources and prepare. Moreover, the longstanding integration between China and the global tech industry has enabled them to amass the necessary knowledge and talent to build a self-reliant tech ecosystem.

The key to SMIC’s technological breakthrough in supplying advanced chips to Huawei lies with co-CEO Liang Mongsong, a renowned figure in the chipmaking industry from Taiwan. His extensive experience at Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) and Samsung significantly contributed to SMIC’s success.

Various industry veterans from foreign semiconductor companies, including TSMC, ASML, Synopsys, and Cadence, have joined or started their own ventures in China, further strengthening its tech industry. As long as this free movement of talent continues, enforcing U.S. tech sanctions will remain a formidable challenge.

The U.S. needs to reassess its technology sanction strategy, acknowledging its limitations and potential adverse effects. An overreliance on ineffective measures, such as the sanctions on Huawei, risks undermining Washington’s global reputation.

A more promising strategy would involve a renewed emphasis on increasing investment in research to maintain American technological supremacy and promote innovation. This approach is more likely to succeed and could restore international respect for the U.S.

How it all began

The US-China tech war, which began under the Trump administration and continues under President Biden, is largely a competition for dominance in the technology sector. Originally a trade dispute, it evolved into a battle for leadership in core technologies like 5G, AI, and semiconductors. China, which is making significant investments in efforts to catch up, is currently challenging the US, a global tech leader. As the US blocked China’s access to core technologies, China sought to become more self-reliant. Increased tensions due to the global pandemic led Biden to review US supply chains for critical products, and proposals for significant US investment and R&D spending in core technologies have garnered bipartisan support.

Analysts often cite “Made in China 2025,” Beijing’s 10-year strategy to transform the nation from a large-scale manufacturer to a global powerhouse, as the catalyst for the tech conflict. However, the U.S.’s response was delayed, as the country was preoccupied with the 2016 presidential election when MIC 2025 was unveiled in 2015.

Upon Donald Trump’s election as president, figures like trade advisor Peter Navarro and Senator Marco Rubio criticized MIC 2025 as a blatant example of China’s disregard for international trade laws by subsidizing its tech sector.

The tech war broadened to include a series of disconnected events. These events included fines and sanctions on Chinese telecom firm ZTE for concealing its role in selling U.S. technology to Iran, a report from the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) on China’s alleged intellectual property theft and forced technology transfers, and apprehensions about Huawei Technologies Co.’s supremacy in 5G technology. These events resulted in a wider tech war that received bipartisan backing.

What is China doing to reduce the impact of US actions?

China has implemented various measures in response to U.S. tech-related actions. Firstly, the country’s antitrust authority has blocked corporate mergers involving U.S. semiconductor firms operating in China, disrupting their ability to acquire innovative technology and alter their business strategies. This action notably impacts Intel’s planned $5.4 billion acquisition of Tower Semiconductor. Secondly, China initiated a cybersecurity review of Micron, a prominent U.S. memory chip manufacturer, banning its chips from China’s critical infrastructure sector. While framed as a cybersecurity measure, it is widely understood as political retaliation.

Lastly, China announced new export license requirements for gallium and germanium, essential raw materials for electronics production. As the leading global supplier of these materials, China can now inhibit exports at will. This move is seen as a response to U.S. actions taken on October 7. These measures highlight China’s strategic response to U.S. sanctions in the semiconductor industry.

China’s restrictions on gallium and germanium, essential for electronics production, are not a significant threat due to the availability of these minerals elsewhere. If China restricts exports, the U.S. and other non-Chinese mining companies could enter the market. Even if China uses its dominance in rare-earth metal mining and refining as a threat, the potential for non-Chinese substitutes exists. This scenario would require political will, not just technological feasibility. If China restricts its rare earth supplies, it would raise questions about its reliability as a supplier in all sectors. As a result, global policymakers and corporations are diversifying their trading relationships. Companies like Samsung and Dell have already moved production away from China or plan to do so.

However, retaliation is not the core element of China’s approach. There are four critical components of China’s revised strategy for semiconductors that truly stand out:

China is evading chip export controls by smuggling in advanced AI chips, betting on finding loopholes in the U.S. Department of Commerce’s enforcement barriers. Additionally, it is working to divide the U.S. from its allies by turning its attention to other countries in Europe and South Korea, potentially combining their technical expertise with Chinese resources to pose a serious threat. Additionally, China has escalated its industrial espionage and talent recruitment efforts, with companies like ASML facing thousands of cybersecurity incidents each year.

Most importantly, China is investing heavily to build an all-Chinese supply chain that eliminates dependence on foreign technology suppliers, a move that predates the Biden administration’s export controls. The Chinese semiconductor industry aims for the “replacement of imports with Chinese-made products,” in line with the “self-reliance” goals of China’s Made in China 2025 policy. Despite the policy no longer being openly discussed, it continues to guide China’s tech strategy.

China’s decoupling strategy, which is closer to reality than the Biden administration’s erroneously labeled efforts, has made it harder for China to succeed due to the October 7th export controls blocking access to chip-making equipment. German and South Korean firms should be wary of transferring technology to Chinese competitors for short-term profits, as this would help build a Chinese future where non-Chinese companies have no significant long-term role.

China’s retaliatory measures, designed to intimidate the U.S. and its allies, are creating fear among policymakers, especially in key undecided countries like Germany and South Korea. However, the major strategic concern is China’s long-standing policy to eliminate foreign firms from its tech supply chains and the risk of an authoritarian superpower dominating AI’s future. Although it’s unlikely that the U.S. and its allies will persuade China to abandon these goals, standing strong together can ensure the failure of China’s strategy.

Parties affected by the tech war

South Korean tech giants Samsung and SK Hynix have heavily invested in China, but their commercial ties are strained due to geopolitical tensions. The U.S. has implemented steps to limit China’s access to advanced chips, a move that has repercussions for South Korea’s semiconductor industry, which is crucial for its economy. Uncertainty looms as a one-year waiver from these export restrictions is due to expire soon.

According to South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol, geopolitical challenges have grown to be a significant risk for businesses. The semiconductor manufacturing process involves global supply chains and the new restrictions have challenged alliances across Asia, Europe, and the U.S. South Korea is among the countries grappling with the potential economic disruption due to these trade restrictions.

China is a significant consumer of South Korean chips, with both Samsung and SK Hynix operating large production sites in China. Semiconductors comprise 20% of South Korea’s exports, with Samsung and SK Hynix leading the memory chip market. Over half of South Korean chip exports have been to China in the past decade, though this dropped to 55% in 2022. Samsung’s chip-related subsidiaries in China reported a 35% sales drop in the first half of 2023 due to reduced chip demand and China’s economic slowdown. SK Hynix’s China revenue, which peaked at 47% in 2019, fell to 27% in 2022.

The China-US tensions bring uncertainty for tech giants like Samsung, SK Hynix, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, with decisions on export restrictions pending from the US Department of Commerce. As a result, these companies may have to change their business strategies in China. Options include focusing production on less advanced products to avoid restrictions or serving Chinese customers from their factories within China. In response to the uncertainties and a temporary dip in chip demand, SK Hynix has scaled back its capital spending in 2023, and construction on its plant in Dalian,China, has stalled.

To counter these challenges, South Korea is planning to boost its domestic chip-making capabilities by creating a semiconductor “mega-cluster” in Yongin, while Samsung and SK Hynix are investing heavily in South Korea and the US. However, aligning too closely with the US could risk economic retaliation from China.

The role of AI in this tech war

In this technological Cold War, artificial intelligence and quantum computing have emerged as the new nuclear weapons of this era. The question arises whether the US can effectively hinder China’s progress in these areas, reminiscent of their unsuccessful attempt to prevent the Soviet Union’s nuclear advancement. Trade sanctions, which have struggled to suppress even Russia’s underdeveloped economy, are unlikely to significantly impede Beijing. Additionally, China has a history of ignoring intellectual property laws in order to get around things it cannot produce or buy, as seen in its treatment of Uyghur culture.

In the context of this technological rivalry, the evolution of AI and other futuristic technologies in China is of paramount concern to the administration, which views Beijing as its chief international strategic adversary.

In an attempt to curb China’s progress, Washington has imposed restrictions on chip exports to the country and levied sanctions on specific Chinese firms. Despite these measures, Chinese tech leaders have still achieved substantial advancements.

In a recent development in October, the US further tightened its control measures to encompass a broader range of chips, equipment, and geographical locations. A primary focus of this update was on companies headquartered in China but operating in over 40 countries, with the aim of preventing these firms from using other nations as middlemen to procure semiconductors that are inaccessible within their home country.

To sum up, the ongoing tech war between the US and China signifies a significant change in global power dynamics, with technology becoming the main platform for competition. The ability of Chinese tech firms like Huawei to bounce back despite the severe US sanctions highlights the limitations of such tactics and underscores China’s progression towards self-sufficiency in technology, with potential repercussions for the global tech scene. At the same time, the fallout from this dispute on other technologically advanced countries like South Korea underlines the wide-ranging impact of this conflict. As AI and quantum computing become the new battlegrounds, the stakes in this tech war continue to rise. The management of this complex situation will necessitate a careful mix of innovation, cooperation, and strategic policy-making from all parties involved.

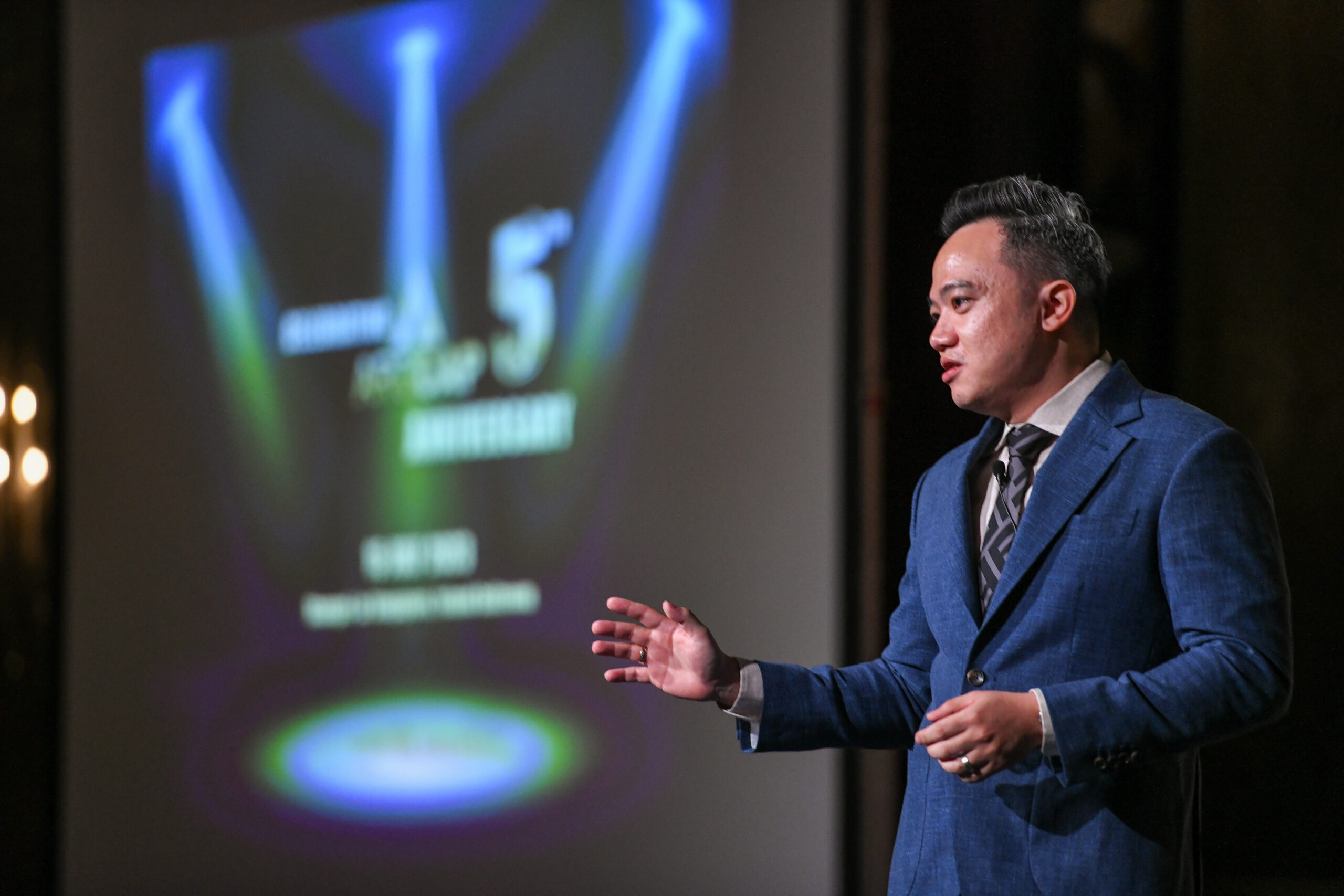

A Trader’s View

Since this article is regarding the US-China tech war, we shall look into USD/CNH, which represents the US dollar against offshore Chinese Renminbi. It would be interesting to look into this currency pair since China is the second-largest economy, behind the United States. In 2023, the US dollar outperformed the CNH. In my opinion, the trend could continue in 2024. The US economy has been one of the outperformers in 2023, with the economy growing at a 2.4% pace that well surpasses the 0.4% consensus growth forecast since the start of 2023. Given the backdrop and economic challenges in Europe and China, it is not surprising that the majority of cross-border funds flow into the US, which could foster continued interest in US assets among foreign investors. To me, towards the end of 2023, the USD has weakened against most currencies as a form of retracement, and there are signs that the US dollar is picking up its strength since the start of 2024.

Let’s look at the technical chart for USD/CNH below.

USD/CNH H4 Chart

From the above H4 chart for USD/CNH, it is currently trading at around 7.2075. From a technical point of view, there is a bullish bias since there is an upward channel formed (purple channel). We could expect the price to trend up towards the first target level at around 7.2681. Furthermore, there seems to be an inverted head and shoulder formation (green lines) forming, and we could possibly see further upside potential to the 7.3447 level (top red line) if the price were to break above the neckline of the inverted head and shoulder (black line).

Tan Zheng Xiang